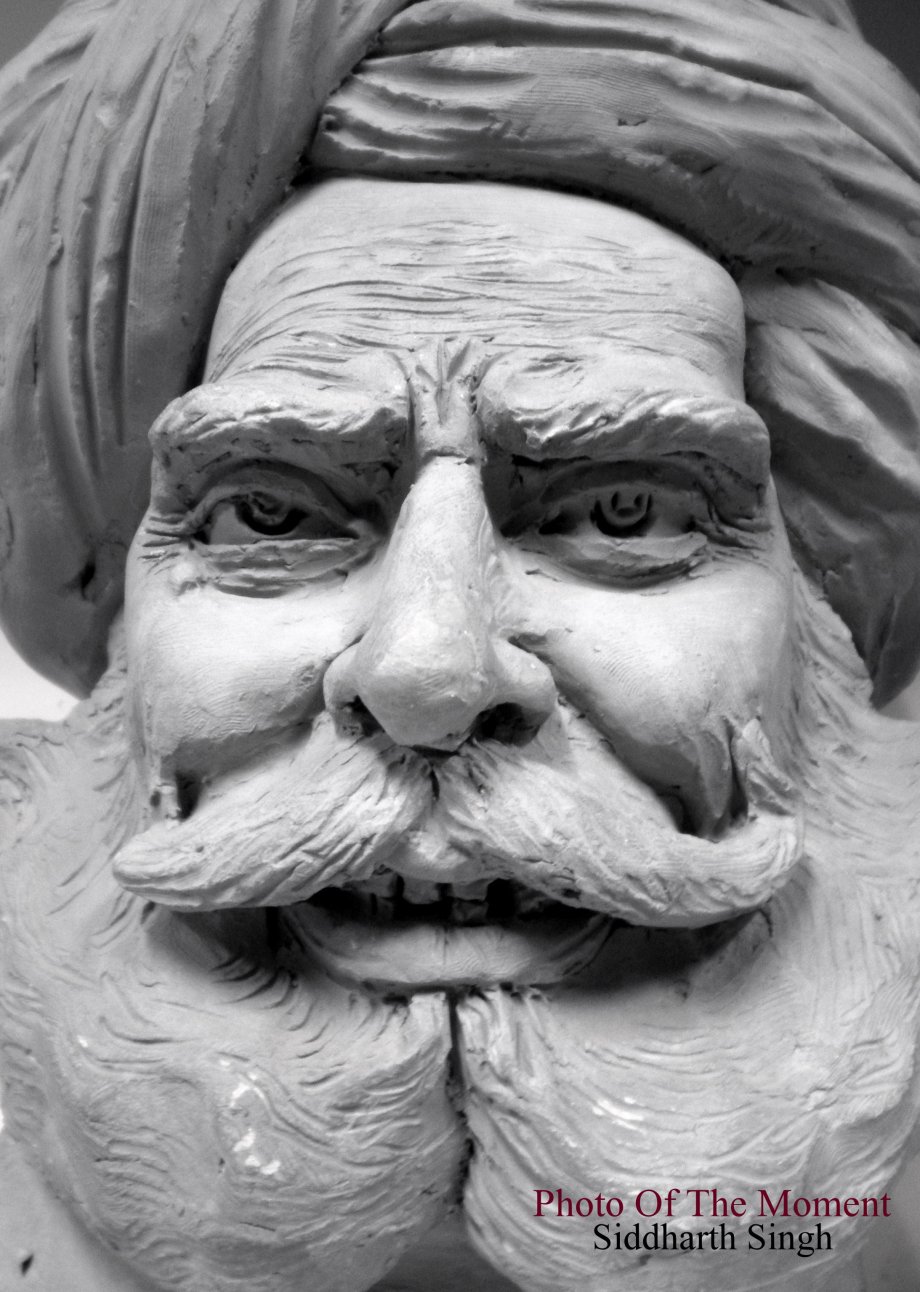

Humayan Ka Makbara, New Delhi, India. By Siddharth Singh (c) 2009

Humayun Ka Makbara in Nizamuddin, New Delhi, is the most beautiful undiscovered-to-Indians Mughal monument in India. And I would go to the extent to say it is beautiful because it is not frequented by us Indians. Littered sidewalks, names etched on the walls of monuments, etc are unheard of here. The surroundings are clean and uncrowded. But mentions in international travel books makes it a hotspot for foreign tourists.

Another very well maintained and relatively undiscovered monument is the Akbar Ka Makbara in Agra. It has beautiful gardens with deer, peacocks and other animals. A delight to those looking for a peaceful evening around a majestic historical monument.

Fatehpur Sikri, which everyone headed for the Taj Mahal in Agra almost certainly visits, on the other hand, is ill maintained. Foul odors, garbage, filth and grime are the order rather than the exception there. Very very avoidable.

If only we respected our history by respecting the relics of the past. Keeping the environs clean surely isn’t that hard an ask.